Even before he laid eyes on it, C.M. Russell was in love with the West. Growing up near St. Louis, Missouri, young Charlie thrilled to tales of Western heroes like Daniel Boone, Kit Carson and Jim Bridger, and even many celebrated members of his own family. A great-grandfather, Silas Bent, had been in charge of surveying the Louisiana Territory, and his son, William Bent, built a trading post – Bent’s Fort – on the Santa Fe Trail.

Young Charlie was determined to follow their lead. As boys, he and his brothers made headdresses of chicken and turkey feathers, applied clay “warpaint” to their faces, and pretended to be cowboys roping cattle and battling Indians. Such an active fantasy life did little to endear him to his teachers. He found the confinement of the schoolroom intolerable so long as the great outdoors beckoned.

Just before his sixteenth birthday, Charlie’s parents surrendered to the inevitable and gave him permission to head West with a family friend. Charlie found work on a sheep ranch in Judith Basin, Montana, but not for long. He was assigned to tend the sheep, but he later admitted that he would lose them “as fast as they’d put ’em on the ranch.” Soon finding himself out of a job, he took up with a professional hunter named Jake Hoover, from whom he learned trapping, hunting, and frontier cooking, but best of all the fine art of storytelling.

In 1882, he landed a job as a horse wrangler on a Montana cattle drive, despite the reputation he’d earned herding sheep. On learning that Charlie would be watching the horses, one cowhand remarked, “I’m betting we’ll be afoot in the morning.” In fact, Russell took to the work and stayed with it for eleven years.

Nicknamed “Kid Russell” because of his tender years, Charlie was a favorite among the cowhands, who enjoyed his abilities as a storyteller and artist. By night he watched the horses and cattle, and by day he sat and sketched the cowhands at work and play. He carried pencils and brushes in a sock hung from his saddle horn, and when paper was scarce, he improvised with wooden boxes, cardboard, or buckskin.

This was the life Charles M. Russell had always dreamed of, but it didn’t last forever. A terrible blizzard in the winter of 1886-87 signaled an end to the days of the open range, as cattle froze and starved in huge numbers. In the future, cattlemen would fence in their lands to better tend their livestock, reducing the need for cowhands and nighthawks. When the cattle’s owner wrote that winter, asking about the condition of the animals, Russell replied by sketching a skeletal steer drooping in the deep snow with hungry wolves ready to take advantage of the steer’s poor condition. He called it “Waiting for a Chinook.”

The image said more than words ever could, and became well known in Montana. It also represented a turning point in Russell’s life. With the cattle business changing and the Judith Basin filling with settlers, his cowboy days were numbered. But a second career beckoned – that of an artist. For the rest of his life, he would combine his two loves, painting and sculpting masterpieces that expressed his fondness and longing for the West that was passing.

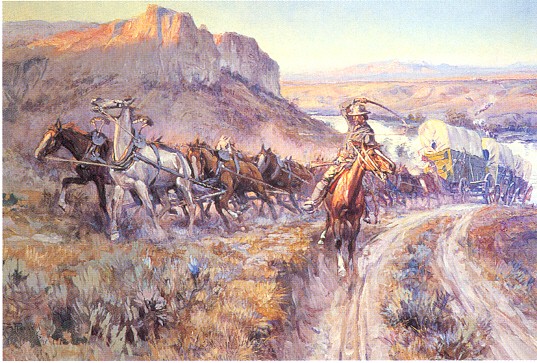

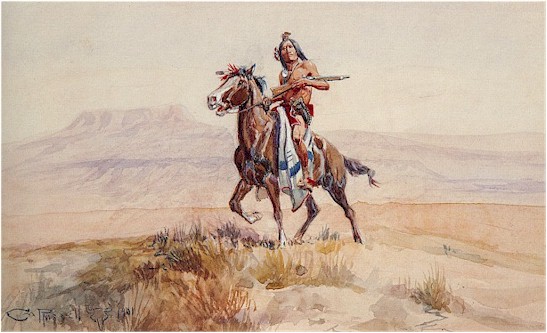

Drawing on Western lore and his own experiences, Russell painted dramatic scenes of cattle drives, bronco-busting and shoot-outs, and quieter scenes from the everyday life of the Plains Indians or cowpunchers, and the Western landscape with its abundance of wildlife. At first, he practically gave his work away, trading it to pay for bills or groceries. In 1896, he married Nancy Cooper, and life soon changed as Nancy took the reigns in managing his career. She recognized the true worth of Russell’s art, and was determined to see that he got a fair price and the recognition he deserved.

As Nancy raised the prices on Charlie’s pieces, there was always a willing buyer, leaving Charlie shaking his head in disbelief. In 1911, a one-man show at New York’s Folsom Galleries put Russell “on the map” in the art world, and soon after came shows in Canada and England. People showed up to see the artist as much as his art: Charlie was a gifted storyteller, and he dressed as a cowboy with boots, a hat, and his trademark red sash which he always wore, even at formal occasions.

Even though he traveled to far off places and met celebrities and millionaires, Charlie was always happiest back home in Montana, and especially in his log studio built with cedar telephone poles. The studio was decorated with cowboy gear and Indian artifacts which Charlie used as references when he wanted to ensure accuracy in his paintings and sculptures. Here, too, was a place where he could socialize. “The bunch,” he said, “can come visit, talk and smoke, while I paint.”

Admired as he was for his talent, C.M. Russell was loved for his character. He was known by all as a true and devoted friend, and was a vocal supporter of rights for Indians long before others joined the cause. His protégé Joe De Yong once said, “most people have a front and back door to their character, but Russell’s was like an Indian teepee – there was only one door and it faced the rising sun. You always knew where to find him and he never changed.”

When the great “Cowboy Artist” passed away in 1926, the world mourned. Horace Brewster, his first roundup boss, remarked that Russell “never swung a mean loop in his life, never done dirt to man or animal, in all the days he lived.” Russell’s creations were his legacy to future generations. In his paintings, sculptures, and writings, he left a chronicle of the American West, his first and longest-lasting love. Thanks to him, it was a love passed on to millions around the world.